Over the past month, I’ve been working on a couple of game projects — an interactive tale based on a classic folk tale and a narrative adventure. The first of these has been completed and launched and the second is currently in development.

Bluebeard: An Interactive Tale

After oodles of work, I finally completed my first Twine interactive tale. Bluebeard: An Interactive Tale is based on the French folk tale, “Bluebeard,” relating the story of a young woman who weds a wealthy man harboring deadly secrets.

The interactive tale features a branching narrative with a total of seven possible endings.

It’s been an interesting process adapting a linear tale into a text game with multiple endings (which I plan to write more on later). Along the way, I’ve learned a lot about crafting branching narratives, and I’m so proud of this project.

What Lies Underneath – Development Process

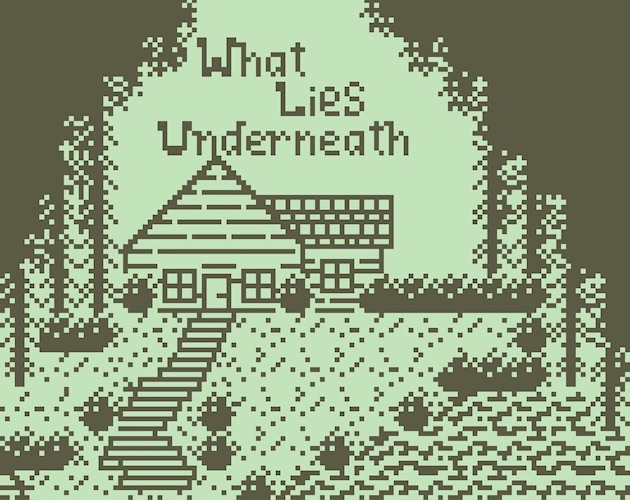

What Lies Underneath is a small narrative game built using the Bitsy game maker (created by Adam Le Doux), an open source tool designed to be simple enough for just about anyone to make their own games.

The game is being developed as part of the Greenlight Jam, which is designed to have participants work through each stage of the game development process — from ideation to prototyping, production, and release of the final product.

Thus far, I’ve worked through the first two stages, ideation and prototyping, for the game, which I shared a little bit about on Itch.io, where you can also play the prototype of the game.