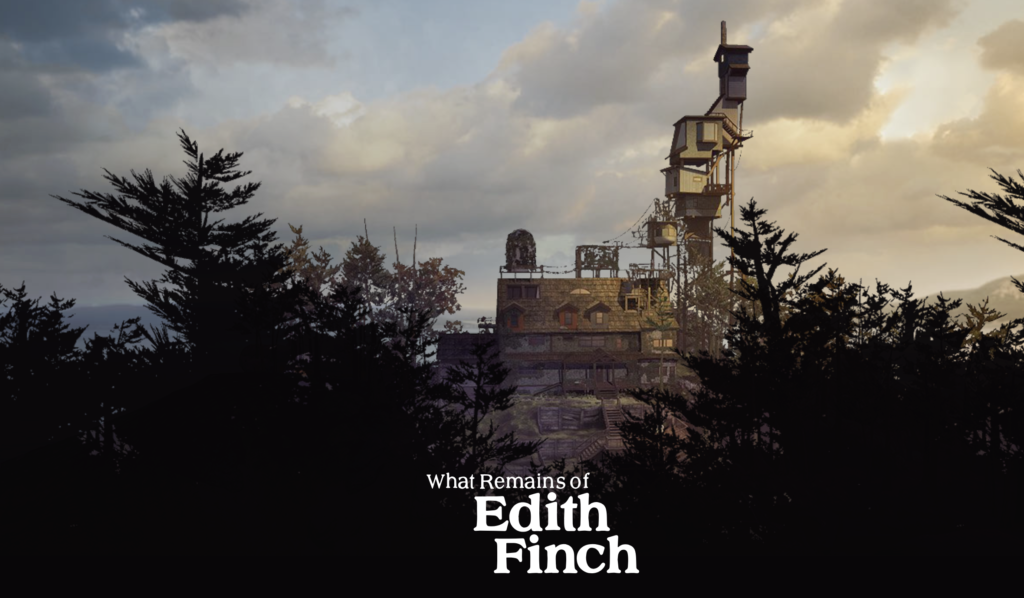

Playing Giant Sparrow’s powerful and moving game, What Remains of Edith Finch, for a second time was just as wonderful and heartbreaking an experience as it was the first. In particular, this second time around, I was impressed by the way the game layers narrative through multiple unreliable narrators.

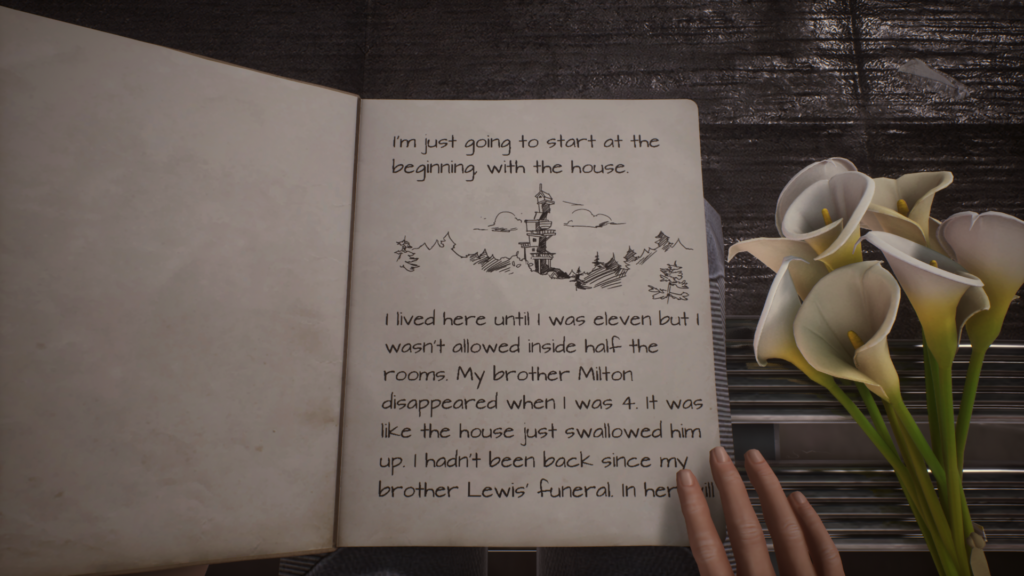

Primarily there is the titular character Edith Finch, who narrates most of the story in a journal. As she returns to her family home — pregnant and uncertain about her future — she explores the house, digging through the objects, photographs, journals, and messages left behind. Her words guide the reader (and player) through the rooms of the house and into the past, as she wonders why her family has maintained such a history of tragedy and loss. Is her family really cursed? Or has her family merely given into the narrative of being cursed, allowing it to lead them become reckless in the way they approach their lives?

Layered into Edith’s remembrances are the journals, letters, and photographs that she finds throughout each of the family members bedrooms — each one left just as it was like a shrine. Each of these mementos connect in some way to the family member’s death, some being memorials (such as poems or letters written about the family member) and others being messages of explanation or forgiveness (such as a footnote left on divorce papers or a note from a psychiatrist), and each one contains its own misconceptions, biases, or just plain idealization of the person writing them.

Reading these passages brings the player into the “memories” of the family member — with the gameplay reflecting the feeling being evoked by the words (with the memories of Edith’s brother Lewis Finch working in a cannery while simultaneously living a vivid fantasy life breaking me all over again). There a feeling of folklore in this exploration, of fairy tale and a kind of magic, even if that sense of magic is only in the eye of the beholder. We tend to see people with a golden perspective after their death, even when tragic, and that is the feeling here.

Even when considering Edith’s journey through the house, portrayed through the words in her journal, the player can notice that the house — which she has not visited in years — remains pristine. There is no dust, no decaying of fabric. No spiderwebs line the corners of the room, no rats have made home in the piles of books. The house and all of its contents remain preserved, much like the way Eddie tried to preserve the memories of her dead family members by creating shrines of their bedrooms.

What Remains of Edith Finch is a stunning exploration of memory and the kind of mythologies families build up around themselves. If the Finch family had not held so tightly to the idea of a generational curse brought over from Europe, if they had not clung to the memory of death so tightly (having built a cemetery before their own home), if they had let go of the past and looked to building a future, would more of the members of the Finch family be alive and thriving today?

It’s hard to say. Sometimes bad things happen, and sometimes they happen repeatedly over and over again to the same family to the point it almost feels like a curse. Sometimes — curse or no — the people in a family need to move on and get busy with the act of living instead of clinging to the past.

I love What Remains of Edith Finch. It’s one of those games that brings me into the realm of sorrow and longing in such beautiful ways that I find myself wanting to wash myself in the experience again and again. I cannot recommend this game highly enough.

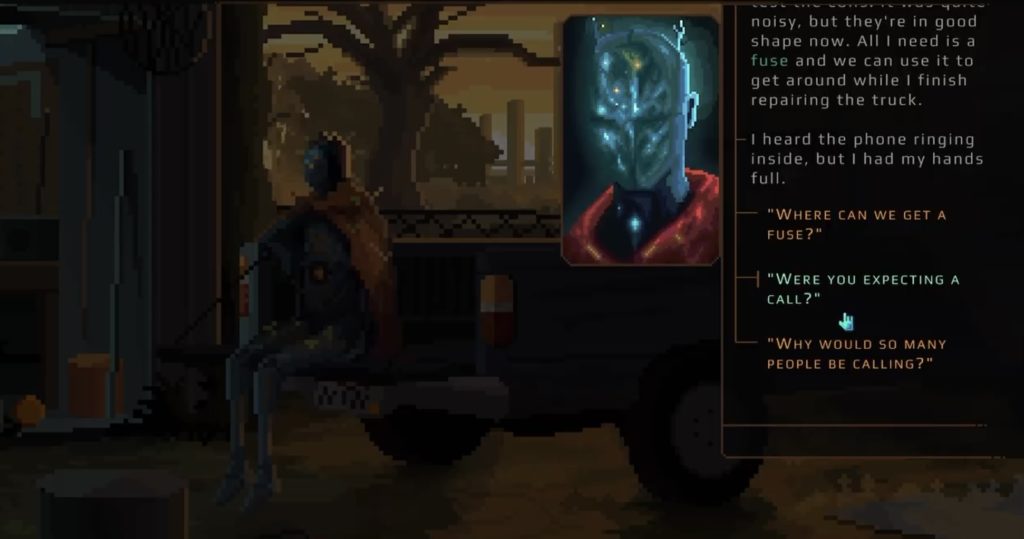

Another fantastic game that I played this month was Norco, a point-and-click adventure game developed Geography of Robots. Set in a near-future New Orleans with communities ravaged by climate change and advanced technologies being utilized by mega-corporations to replace workers, Norco feels like a blend of the dystopian, cyberpunk, and noir genres.

Kay returns home after her mother died of cancer and finds her brother missing. With the help of a cybernetic robot that lives with the family, she searches for her brother — and along the way she delves her mother’s research into strange the strange things happening in Lake Pontchartrain, discovering corporate espionage, sentient AI systems, and mysterious objects from beyond human understanding.

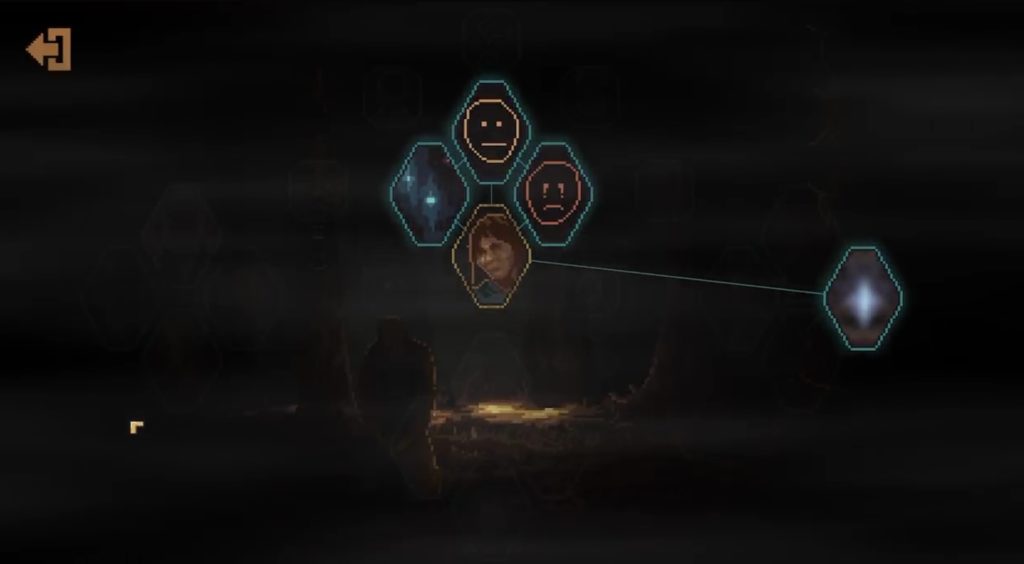

The game involves moving through various maps, talking with various shady characters, and solving light puzzles. In particular, one of my favorite narrative and gameplay elements is the mind-map. During conversations, Kay will learn new clues (names, locations, and other elements). The player is then able to open up her mind map and make connections between these elements, which provides greater insights into how Kay perceives certain characters and situations, as well as opening up new areas of the game.

I dig the weirdness of Norco — the way it can go into the high strangeness of science fiction, while at the same time being grounded in the gritty reality of a world that leaves workers and disenfranchised folks to live in the mud and muck of flooded homes, a lack of viable work due to computers replacing workers, escape through drugs, and other major issues that arise when profit overtakes humanity. A fantastic game.

I also started playing Inmost, a narrative puzzle platforming game from Hidden Layer Games. The game features some beautiful pixel art and some fun platforming elements — and I’ll talk about it more next month, after I’ve completed the game.

And Books, too…

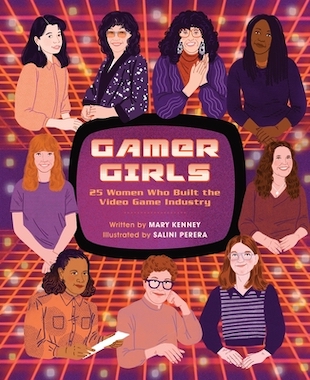

Written by Mary Kenney and paired with beautiful illustrations by Salini Perera, Gamer Girls gives a look into game development history, sharing the stories of many of the women who helped shape the world of board and video games, from the early days of programming to the present day. Each short chapter tells the story of how the designer, artist, songwriter, or storyteller came to video games and the challenges they faced in creating and developing their work and careers.

Very inspiring.

.

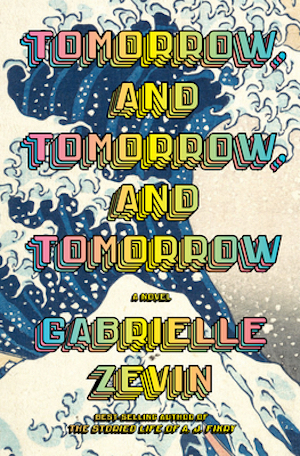

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle ZevinTomorrow (which I read in June) is one of my favorite reads of the year. The story centers on Sam Masur and Sadie Green, two friends who bonded over playing video games as kids before having a falling out, leading to them not speak to each other for years. When they stumble into each other while at college, they renew their friendship and love for games and enter into a wild adventure — make their own video game, a wild, risky, wonderful challenge. As the novel weaves through their game development and business successes and failures together, the story beautifully explores the nature of creative processes and partnerships and the ups and downs of close friendships, along with love, ego, grief, and so much more.

A lot of the books I love are well written, but it’s not often that I pause while reading a passage and go, woah. Zevin’s writing style is delicious. The omniscient third person perspective (used through most of the book) allows the author to float between the inner worlds of each of the characters, giving insights that they may not even recognize themselves. This is a genuinely gorgeous book, a new favorite read, and one that I will be returning to again and again.

If you’d like to know about the rest of books and moves I read recently, you can check out my Culture Consumption for July.