By the time I got around to Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy (which I’m playing on my phone using the touchscreen), I was well aware of the game’s reputation for inducing rage and frustration in its players. I had watched a number of Let’s Plays, in which gamers (particularly Markiplier) lost their cool, screaming in rage as they failed over and over again.

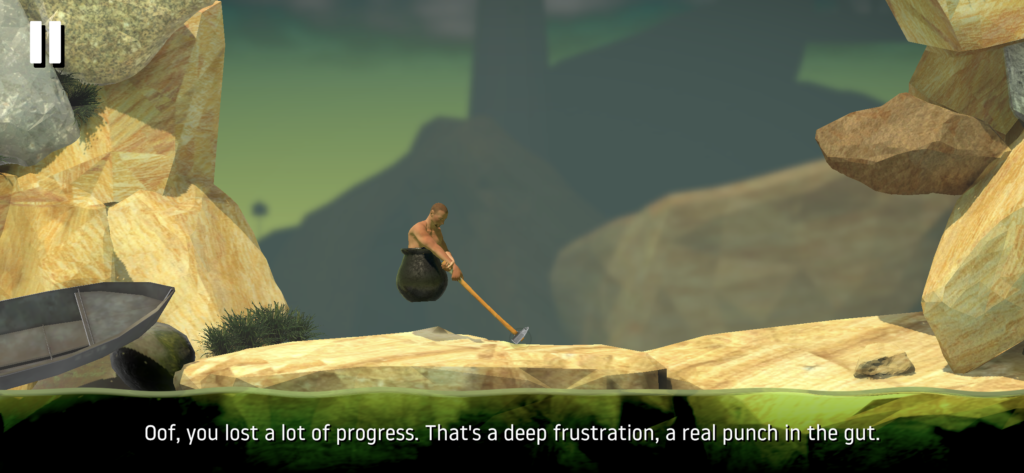

The game is based off a simple mechanic: a man in a cast-iron pot swings a hammer to climb the mountain — but its actual execution is exceedingly difficult. The hammer doesn’t swing the way you expect it to, and it takes a significant amount of trial and error to simply figure out how it functions and get over the first tree you encounter in the game. Not to mention the increasingly difficult challenges that lie ahead.

I’ll write a bit more about my ongoing struggle with trying to beat the game (I am very stuck at the moment) and how it makes me feel in another post. Short version: it is indeed frustrating, but in a way that I personally find oddly satisfying.

For the moment, I’d like to focus on the way Getting Over It approaches game writing — rather than providing a traditional narrative, the game presents a more philosophical approach. When the game opens up and the player faces the first obstacles, Bennett Foddy begins his narrations by warning the player about the challenges ahead:

Starting over is harder than starting up. If you’re not ready for that, like if you’ve already had a bad day then what you’re about to go through might be too much. Feel free to go away and come back. I’ll be here.

He then begins discussing his inspiration for Getting Over It, notably a game titled “Sexy Hiking,” by the creator Jazzuo. He discusses the deeply frustrating challenges of this earlier game, and it’s place as a B-game, which is essentially “a rough assemblages of found objects” that is quickly put together and tends to be “too rough and unfriendly to gain much of a following.” Getting Over It stands as a much more polished homage to this earlier game, even replicating the first obstacle of a barren tree.

He discusses his process and how he could have made certain challenges easier, but elected not to seeing the difficult as a fault in his own self as a player, rather than in the game. He also delves into a discussion of the trash culture of our current society, which is wrapped up in “B-games, B-movies, B-music, B-philosophy.” There’s a constant influx of new content, new “trash” and “Everything’s fresh for about six seconds until some newer thing beckons and we hit refresh.”

Some players have called this ongoing discussion pretentious, an attempt to elevate the game beyond what it is — a purposefully and obtusely difficult game. And it is certainly that, but at the same time, the game also seems to align itself with this very same trash culture. Even as it pushes away from making “friendly content” that’s easier to be consumed, the game also presents the visual representation of the trash heap, objects (umbrellas, chairs, slides) stacked on top of each other willy nilly, piles of boxes, rusty refrigerators, and other trash.

Getting Over It is a part of the trash heap, but Foddy notes that although trash may be disposable, “it doesn’t have to be approachable” and he highlights the value of frustration throughout the game — particularly when the player makes a mistake.

When the player inevitably falls off the mountain (over and over again), Foddy jumps in with commentary, quotes from famous folks, and music. Much of this is tongue in cheek, teasing the player about their situation, such as Foddy calling a fall a “real punch in the gut” or quoting Abraham Lincoln stating “You cannot now believe that you will ever feel better. But this is not true. You are sure to be happy again.” or playing the song “Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad” by Cliff Carlisle.

Most of these quotes and songs deal directly with overcoming failure and/or expressing a sense of shared pain. They note the importance of trying and not giving up and the value of working through hard feelings. As Foddy states, “Don’t let it get to you. But also… let it get to you a little bit,” because the frustration and struggle are a part of the experience.

For many players, this ongoing commentary only added to the ongoing frustration. (For example, I can’t help but think of Markilplier yelling, “I know you know you’re making it worse,” as he attempted the same obstacle for upteenth time.)

However, for me, I found these moments of commentary to be comforting. When Foddy pipes in to quote Friedrich Nietzsche stating “To live is to suffer,” I couldn’t help but smile and think to myself, yeah, it do be that way sometimes. And in the end, my greatest moments of frustration and upset came after I managed to fall off the mountain so many times that Foddy’s commentary went away, leaving me with nothing but the silence and quiet grunts of the man in the cauldron trying to once again make it up that mountain.

I’m not entirely sure what it is about this game that provides me with pleasure throughout the entire frustration-inducing experience. Part of it may be the way this game feels like it reflects my own creative life at the moment — how no matter how many times I approach the mountain of my career, I never feel like I’m making it up that hill (something I plan to write more about later).

And just like playing Resident Evil 2 Remake brought me a sense of calm during the intense year of 2020 by offering me a comfortable and manageable anxiety that I could turn on or off at will, Getting Over It seems to bring me a sense of comfort by reflecting the same frustration of seemingly unending struggle in a manageable format that I can put down and walk away from — not to mention the endorphin-inducing triumph of finally overcoming a difficult obstacle, providing a feeling of accomplishment that can be more difficult to recognize in the day-to-day grind of writing, where I rarely have time stop and enjoy the moment, because there is always a next project or assignment that needs work.

As I’m writing this, I have not finished Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy and honestly, I don’t know how long it will ultimately take me to achieve that goal — if I ever do. But I’m still climbing up that hill, and I plan to do so for the foreseeable future.

After replaying What Remains of Edith Finch last month, I decided to jump into The Unfinished Swan (another Giant Sparrow game), because I heard the stories are loosely connected (very loosely so, as it turns out). When you startup The Unfinished Swan, the player is confronted with an entirely blank white space — much like a blank page. In order to discover the edges and borders of this world, the player begins splattering it with black paint, which reveals the hidden world. It’s a fascinating and visually beautiful mechanic.

Throughout the game, the player chases after a swan that escaped an unfinished painting — and the story unfolds like a child’s fair tale about a King who created this fantastical world with the aim of evoking beauty and order. The journey carried through labyrinths and cities and dark (and genuinely scary) forests. The mechanics and puzzles shift from level to level, but never become too challenging, and the conclusion is satisfying for this particular tale.

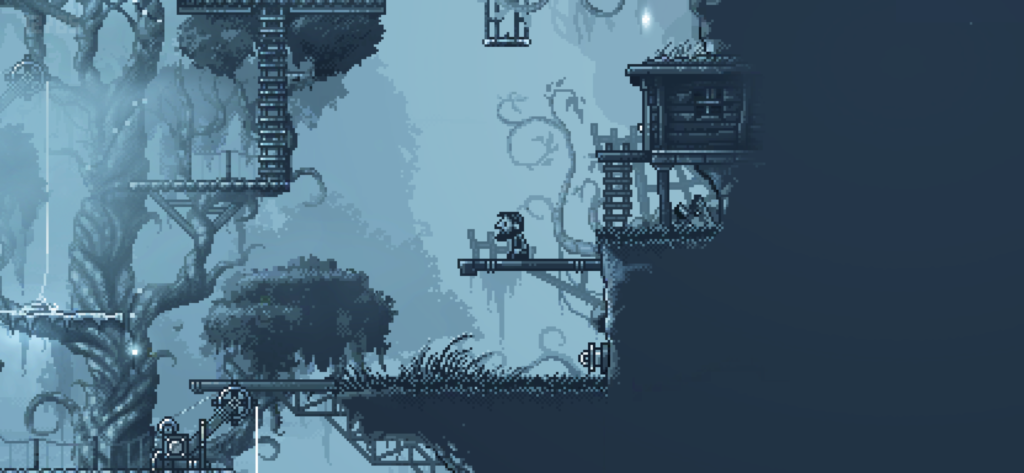

Inmost (Hidden Layer Games) is a side-scrolling puzzle platformer with gorgeous pixel-style artwork. The game essentially follows three storylines, each presenting slightly different mechanics. First, is that of a man journeying through the ruins of nightmare world, progressing through various puzzles to reach new areas — and this is the main storyline. Second, is that of a small child playing in her family home and backyard, in which movement is limited by her small size and strength. Third, is that of a mysterious white knight who fights his way through various shadow creatures.

The game explores dark themes, in particular depression and suicide, through the lens of a shadowy fairy tale world. I found the shift in perspectives and mechanics to be an interesting addition, providing some depth to the scenes as I tried to work out how it all fit together. However, the writing style was a bit on the nose for my personal taste (mostly in regards to constant mention of pain and how people in this world cause pain in orders to gain their own power). Nevertheless, I enjoyed the gameplay and am glad I gave this one a try.

Outlanders (Pomelo Games), which I have mentioned before, has become my new go-to phone game. I turn to it whenever Two Dots is out of levels for me to play. I enjoy the puzzle of keeping the community alive and growing, while gathering specific resources for whatever goals are at play.

If you’d like to know about the rest of recent culture I consumed, including books, movies, and TV, you can check out my Culture Consumption for August.

Extras

Over this past month, I listened to two fascinating games-related podcasts. The first is “For Amusement Only” on 99 Percent Invisible, which explores Pinball’s seedy history. In fact, it was considered so questionable that it was even banned in a number of cities, with it only becoming legal in Alameda, California in 2014.

The second was “Catching the Mind Virus” on Imaginary Worlds, which discusses Ong’s Hat, a made-up cult located in New Jersey that still appears on certain maps, despite the town not existing. Ong’s Hat started as an early internet prank, turned into an elaborate AR game, and then became a conspiracy theory with fans taking it too far.